Tunga Kuhana A

E-mail address: arsene_tunga@yahoo.fr

Tel: +8618595742489

© 2019 Sift Desk Journals. All Rights Reserved

VOLUME: 4 ISSUE: 4

Page No: 487-503

Tunga Kuhana A

E-mail address: arsene_tunga@yahoo.fr

Tel: +8618595742489

Tunga Kuhana A.a, Jason T. Kilembea, Aristote Matondoa, Khamis M. Yussufb, Lauraine Nininahazweb , Fils K. Nkatua, Milka N. Tshingamba, Emmanuel K. Vangua, Junior T. Kindalaa, Shetonde O. Mihigoa, Sungula J. Kayembea, Yves S. Kafutia, Agboyibor Clementb, Kalulu M. Tabaa

a Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Sciences, University of Kinshasa, P.O Box 190, Kinshasa XI, Democratic Republic of Congo

b School of Pharmaceutical Science, Zhengzhou University, 100 Kexue Avenue, Zhengzhou, Henan 450001, China

Joaqun Maria Campos Rosa(jmcampos@ugr.es)

Oniga SD(smaranda.oniga@umfcluj.ro)

Mahmoud A. A. Ibrahim(m.ibrahim@compchem.net)

Meeran SM(s.musthapa@cftri.res.in)

Jason T. Kilembe, Aristote Matondo, Khamis M. Yussuf, Lauraine Nininahazwe, Fils K. Nkatu, Milka N. Tshingamb, Emmanuel K. Vangu, Junior T. Kindala. Shetonde O. Mihigo, Sungula J. Kayembe, Yves S. Kafuti, Agboyibor Clement, Kalulu M. Taba, Tunga Kuhana A. Computational analysis by molecular docking of thirty alkaloid compounds from medicinal plants as potent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease(2020). JCCMM 4(3):487-503

Year 2020 has been highly affected by the COVID-19 outbreak. The urgent need for a potent and effective drug for the treatment of this malignancy put pressure on researchers and scientists worldwide to develop a potential drug or a vaccine to resist SARS-CoV-2 virus. We report in this paper the assessment of the efficiency of thirty alkaloid compounds derived from African medicinal plants against the SARS-CoV-2 main protease through molecular docking and bioinformatics approaches. The results revealed four potential inhibitors (ligands 18, 21, 23 and 24) with 12.26 kcal/mol being the highest binding energy. Additionally, in silico drug-likeness and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity) properties for the four ligands showed a good predicted therapeutic profile of druggability, and fully obey the Lipinski's rule of five as well.

Coronaviruses have recently become a serious problem in the world. They belong to the coronavirinae family which contains four genera based on genetic properties: alpha-, beta-, delta- and gamma-coronavirus. Approximately, the genome size of coronavirus compared to other RNA viruses ranges from 26 to 32 kilobases. The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) also belong to the beta-coronavirus genus and are zootopic pathogens that can cause severe respiratory diseases in humans [1,2].

The novel coronavirus pneumonia (coronavirus disease 2019, COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2) is a highly contagious acute respiratory infectious disease and constitutes a major public health problem. The nucleic acid of the novel coronavirus is a positive-stranded RNA [3]. Its structural proteins include spike protein (S), envelope protein (E), membrane protein (M), and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein; while its transcribed non-structural proteins include: ORF1ab, ORF3a, ORF6, ORF7a, ORF10 and ORF8. The novel coronavirus is highly homologous to the coronavirus in bats [4,5], and has significant homology with the SARS virus [6-8]. It was first detected in December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei Province (China), and became a global pandemic, killing hundreds of thousands of people [9]. The infected patients by SARS-CoV-2 have a fever and a temperature above 38°C with symptoms such as dry cough, fatigue, dyspnea, difficulty breathing, and various fatal complications including organ failure, septic shock, pulmonary edema, severe pneumonia, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) [10].

There are only two ways of transmission of COVID-19 that have been reported, by droplets and contact (direct and indirect) [11].

Currently, there are no specific treatments available for COVID-19 and several explorations relevant to the therapies of COVID-19 are becoming inadequate [12]. Consequently, other than vaccine development, academics and researchers have undertaken several strategies, by using on one hand traditional medicinal plants as possible alleviating drugs [13-14], and one the other hand by exploring in silico studies to pinpoint potential inhibitors from a set of secondary metabolites and other chemical compounds [15-16]. Nevertheless, it is worthy to mention that some studies have encountered the combinations of existing drug candidates (FDA approved drugs) involving anti-HIV drugs such as lopinavir/ritonavir, remdesivir, etc for therapeutic use against COVID-19 [17].

The recognition of protease as an attractive target to inhibit COVID-19 replication has emerged as an interesting pathway to investigate both natural and synthetic drugs to target the viral protease [18,19]. Medicinal plants provide a wide variety of integral and alternative drugs which may assist to solve the many puzzles behind several viral diseases [20]. So, the different parts of the plant (stem, roots, seed, bark, food and flower) are used to treat diseases which vary from frequent to rare infectious and non-infectious ailments [21].

In this study, we evaluated the potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease from thirty alkaloid compounds derived from African medicinal plants as one of rich in floral biodiversity and its plant materials are endowed with natural products (NPs) with intriguing chemical structures and promising biological activities which can be used in searching the solution against COVID-19 [22]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 80% of the population in Africa use traditional medicine to solve their primary health problem [9]. A survey of literature allowed us to identify 30 alkaloids compounds derived from plants used in African Traditional Medicine (ATM), harvested from the following countries: Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, Tanzania, South Africa, Ivory Coast West African countries, Kenya and East African countries (Table 1) [22]. These 30 phytochemicals have been put in interaction with the SARS-CoV-2 main protease to assess their efficiency against the virus protease using molecular docking tool, and thus pinpoint the potential inhibitors.

Table 1. Summary of selected alkaloids derived from the African plant: indoles and naphthoisoquinolines

|

Compound subclass |

Isolated metabolites |

Plant species (family) |

Part of the plant studied |

Harvest place (locality, country) |

Reference |

|

Indole alkaloids |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 |

Monodora angolensis (Annonaceae) |

Stem and root bark |

Kiwanda, Tanzania |

[23] |

|

7, 8 |

Isolona cauliflora (Annonaceae) |

Stem and root bark, and flower stalks |

Namikwe Island, Tanzania |

[23] |

|

|

9 |

strychnos usambarensis (loganiaceae) |

leaves |

Akagera National park,Rwanda |

[24] |

|

|

10 and 11 |

Penianthus longifolius (Menispermacea) |

Stem bark |

Cameroon |

[25] |

|

|

12 |

Fagara zanthoxyloides (Rutaceae) |

roots |

Nigeria |

[26] |

|

|

13 |

Picralima nitida (Apcynaceae) |

fruits |

Nnewi, Nigeria |

[27] |

|

|

14 and 15 |

Strychnos usambarensis (loganiaceae) |

leave |

Akagera National park, Rwanda |

[28]

|

|

|

Naphthoisoquinolines |

16, 17, 18,19 and 20 |

Ancistrocladus robertsoniorum (Acistrocladaceae) |

Stems and leaves |

Buda Mafisini Forest, Kenya |

[29] |

|

21, 22, 23 and 24 |

Ancistrocladus tanzaniensis (Acistrocladaceae) |

leaves |

Uzungwa Mountains, Tanzania |

[30] |

|

|

25 |

Triphyophyllum peltatum (Dioncophyllaceae) |

roots |

Parc de Taï, West Ivory Coast |

[31] |

|

|

26 |

Triphyophyllum peltatum (Dioncophyllaceae) |

Root bark |

West Ivory Coast |

[32] |

|

|

27, 28, 29 and 30 |

Triphyophyllum peltatum (Dioncophyllaceae) |

Leaves and Twigs |

Mt. Nabemba, Congo Republica and West Ivory Coast |

[33,34] |

2.1. Receptor preparation

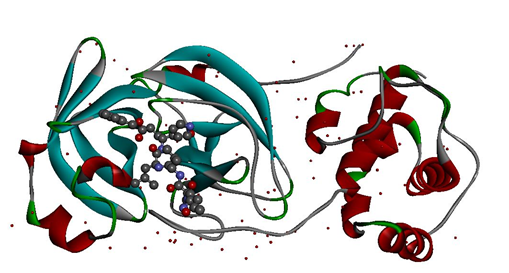

The crystal structure of COVID-19 Mpro (PDB ID: 6LU7) (Figure 1) was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank and imported into Auto dock 4.2 where the inhibitor and water molecules were removed before the docking and hydrogen atoms were added to the protein to correct the ionization and tautomeric states of the amino acid residues. Further, Kollman charges were added and the protein was saved in .pdbqt format [35].

Figure 1. The crystal structure of COVID-19 main protease in complex with the crystallized inhibitor N3

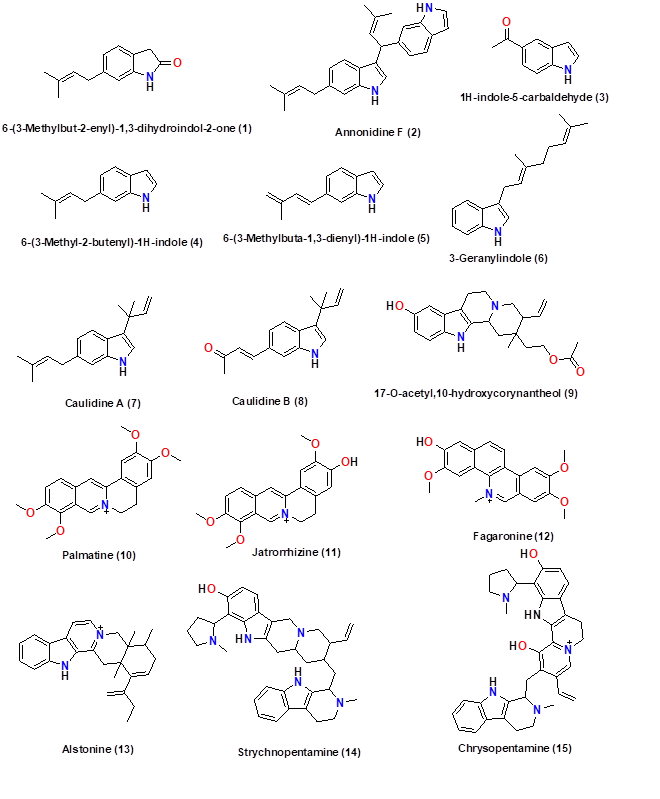

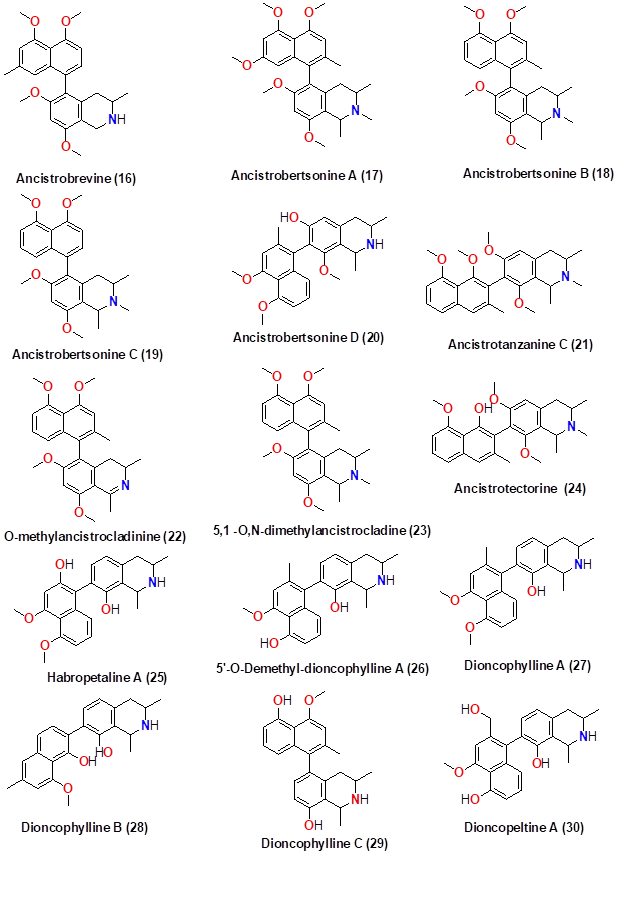

2.2. Ligands preparation and pharmacokinetic study

The selected alkaloid compounds derived from African medicinal plants were drawn using ChemDraw Ultra (8.0). Figures 2 and 3 show the 2D structures of the sketched compounds. From ChemDraw, the 2D structures of ligands were imported to obtain 3D structures. The 3D ligands were then saved in .pdb format for molecular docking with the SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

Since the binding affinity of ligand-protein interactions merely gives an idea of the thermodynamic stability of the formed complex, it is important to analyze the pharmacodynamics of the potential inhibitors. To do so, predictions of ADMET (Adsorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity) of all investigated compounds were assessed through the SwissADME database available at https://www.swissadme.ch, and preADMET server (Korea) [36, 37].

Figure 2. Indole alkaloids derived from the African flora.

Figure 3 Naphthoisoquinolines derived from plants used in African traditional medicine

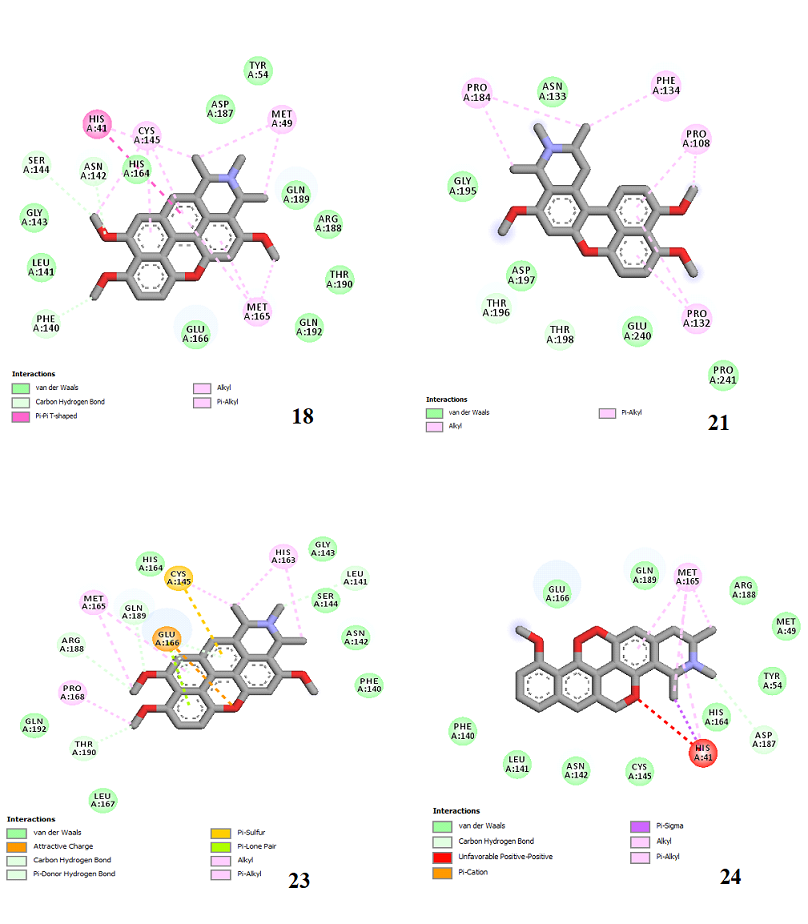

Figure 4. Molecular docking of the four best ligands with Mpro, as potential therapeutic candidates against COVID-19. Interactions of various amino acids of Mpro with ligand 18, 21, 23 and 24 are presented with the best docking pose.

2.3 Molecular recognition ligand-protein by molecular docking

Molecular docking is used to estimate the scoring function and evaluate protein-ligand interactions to predict the binding affinity and activity of the ligand molecule [38]. The Auto dock tool was used to generate the bioactive binding poses of the ligands dataset in the active site of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. The protein coordinates from the bound ligand of 6LU7 were used to define the binding site. So, the scoring function was calculated using the standard protocol of the Lamarckian genetic algorithm [39]. The grid map for docking calculations was centered on the target protein. Accelrys Discovery Studio 2019 software [40] was used to model non-bonded polar and hydrophobic contacts in the inhibitor site of 6LU7. The docking results were visualized using Pymol 2.3.4.0 (see Figures S1 and S2 in supplementary data) and Discovery Studio Visualizer 4.0.

3.1. Energetics and ligand-protein interactions

The docking calculations of thirty alkaloid compounds with SARS-CoV-2 protease were carried out by using the Autodock virtual screening tool. The results of docking calculations in terms of binding affinity (kcal/mol) and interactions of different orientations of alkaloid compounds in the active site of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease are shown in Table 2. Also gathered in this table are the drug-likeness properties of the ligands.

The binding affinity values of the virtual screening between the 30 selected compounds and the SARS-CoV-2 main protease range from 5.52 to 12.26 kcal/mol. It should be noted that the best candidate against COVID-19 is a compound (a hit molecule) that binds to the target (SARS-CoV-2 main protease) and has the desired effect. Thermodynamically, this is a compound with the highest possible binding energy expressed in terms of Gibbs free energy variation (∆G) [9,15]. This allows us to identify in this initial step 22 hits mainly: ligand 2 (7.49 kcal/mol), from ligand 8 (7.88 kcal/mol) to ligand 12 (8.17 kcal/mol), from ligand 14 (9.73 kcal/mol) to ligand 28 (10.70 kcal/mol), and finally ligand 30 (7.81 kcal/mol). These ligands were retained in comparison of their binding affinity with those reported in this paper of the FDA approved drugs used to treat erectile dysfunction (tadalafil : 8.80 kcal/mol) and human immunodeficiency virus/HIV (lopinavir : 8.19 kcal/mol), as well as in comparison with the binding energy of the reference ligand (8.80 kcal/mol). The best-docked compounds (∆G ≤ 8.2 kcal/mol; see also ref. 41) are hits 10 (9.33 kcal/mol), 11 (9.05 kcal/mol), 12 (8.17 kcal/mol), 14 (9.73 kcal/mol), 18 (12.26 kcal/mol), 21 (9.97 kcal/mol), 22 (9.60 kcal/mol), 23 (10.99 kcal/mol), 24 (11.28 kcal/mol), 25 (9.99 kcal/mol), 26 (8.27 kcal/mol), and 28 (10.70 kcal/mol).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first computational study that reports binding energies higher than 10 kcal/mol of ligands to bind to one of the pharmacological targets of the SARS-CoV-2. In fact, Olubiyi and coworkers performed high throughput virtual screening of over one million compounds, but only six with the strongest computed affinities ranging from 8.2 to 8.5 kcal/mol were identified [41].

Table 2. Docking results of alkaloid compounds: binding affinity (kcal/mol), ligands-COVID-19 Mpro interactions and the drug-likeness properties

|

Ligands |

Binding Affinity |

Interaction map between ligands and SARS-CoV-2 main protease |

Drug-likeness properties (Lipinski’s rule of five) |

|

Ref-Ligand |

-8.80 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 779.92 Log P (< 5): 4.51 HBD (< 5): 6 HBA (< 10): 10 MlogP (< 4.15): 0.12 Violations: 3 |

|

Tadalafil |

-8.80 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 391.42 Log P (< 5): 2.83 HBD (< 5): 1 HBA (< 10): 4 MlogP (< 4.15): 1.60 Violations: 0 |

|

Lopinavir |

-8.19 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 628.80 Log P (< 5): 3.44 HBD (< 5): 4 HBA (< 10): 4 MlogP (< 4.15): 2.93 Violations: 1 |

|

1 |

-6.61 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 201.26 Log P (< 5): 2.44 HBD (< 5): 1 HBA (< 10): 1 MlogP (< 4.15): 2.51 Violations: 0 |

|

2 |

-7.49 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 368.51 Log P (< 5): 3.90 HBD (< 5): 0 HBA (< 10): 2 MlogP (< 4.15): 4.83 Violations: 1 |

|

3 |

-5.52 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 159.18 Log P (< 5): 1.51 HBD (< 5): 1 HBA (< 10): 1 MlogP (< 4.15): − 1.18 Violations: 0 |

|

4 |

-5.59 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 185.26 Log P (< 5): 2.46 HBD (< 5): 0 HBA (< 10): 1 MlogP (< 4.15): − 2.95 Violations: 0 |

|

5 |

-5.87 |

|

MW (< 500 Da):183.25 Log P (< 5): 2.42 HBD (< 5): 0 HBA (< 10): 1 MlogP (< 4.15): 2.87 Violations: 0 |

|

6 |

-5.71 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 253.38 Log P (< 5): 3.45 HBD (< 5): 0 HBA (< 10): 1 MlogP (< 4.15): 4.12 Violations: 0 |

|

7 |

-6.53 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 253.38 Log P (< 5): 3.32 HBD (< 5): 0 HBA (< 10): 1 MlogP (< 4.15): 4.12 Violations: 0 |

|

8 |

-7.88

|

|

MW (< 500 Da): 253.34 Log P (< 5): 2.68 HBD (< 5): 1 HBA (< 10): 1 MlogP (< 4.15): 2.88 Violations: 0 |

|

9 |

-7.73 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 368.47 Log P (< 5): 3.15 HBD (< 5): 2 HAD (< 10): 4 MlogP (< 4.15): 2.62 Violations: 0 |

|

10 |

-9.33 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 352.40 Log P (< 5): 0.00 HBD (< 5): 0 HBA (< 10): 4 MlogP (< 4.15): 2.01 Violations: 0 |

|

11 |

-9.05 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 338.38 Log P (< 5): 0.0 HBD (< 5): 1 HBA (< 10): 4 MlogP (< 4.15): 1.78 Violations: 0 |

|

12 |

-8.17 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 350.39 Log P (< 5): 3.32 HBD (< 5): 1 HBA (< 10): 4 MlogP (< 4.15): 2.13 Violations: 0 |

|

13 |

-6.33 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 371.54 Log P (< 5): 0.00 HBD (< 5): 1 HBA (< 10): 0 MlogP (< 4.15): 5.01 Violations: 1 |

|

14 |

-9.73 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 549.75 Log P (< 5): 4.62 HBD (< 5): 3 HBA (< 10): 4 MlogP (< 4.15): 3.51 Violations: 1 |

|

15 |

-7.77 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 560 Log P (< 5): 0.00 HBD (< 5): 4 HBA (< 10): 4 MlogP (< 4.15): 2.77 Violations: 1 |

|

16 |

-7.56 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 407.50 Log P (< 5): 4.26 HBD (< 5): 1 HBA(< 10): 5 MlogP (< 4.15): 2.86 Violations: 0 |

|

17 |

-7.51 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 465.58 Log P (< 5): 4.71 HBD (< 5): 0 HBA (< 10): 6 MlogP (< 4.15): 2.92 Violations: 0 |

|

18 |

-12.26 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 435.56 Log P (< 5): 4.58 HBD (< 5): 0 HBA (< 10): 5 MlogP (< 4.15): 3.26 Violations: 0 |

|

19 |

-7.50 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 421.53 Log P (< 5): 4.42 HBD (< 5): 0 HBA (< 10): 5 MlogP (< 4.15): 3.06 Violations: 0 |

|

20 |

-7.60 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 407.50 Log P (< 5): 4.15 HBD (< 5): 2 HBA (< 10): 5 MlogP (< 4.15): 2.86 Violations: 0 |

|

21 |

-9.97 |

|

MW(< 500 Da): 435.56 Log P (< 5): 4.35 HBD (< 5): 0 HBA (< 10): 5 MlogP (< 4.15): 3.26 Violations: 0 |

|

22 |

-9.60 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 419.51 Log P (< 5): 4.14 HBD (< 5): 0 HBA (< 10): 5 MlogP (< 4.15): 2.99 Violations: 0 |

|

23 |

-10.99 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 435.56 Log P (< 5): 4.58 HBD (<5): 0 HBA (< 10): 5 MlogP (< 4.15): 3.26 Violations: 0 |

|

24 |

-11.28 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 421.53 Log P (< 5): 4.31 HBD (< 5): 1 HBA (< 10): 5 MlogP (< 4.15): 3.06 Violations: 0 |

|

25 |

-9.99 |

|

MW(< 500 Da): 379.45 Log P (< 5): 3.78 HBD (< 5): 3 HBA (< 10): 5 MlogP (< 4.15): 2.44 Violations: 0 |

|

26 |

-8.27 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 363.45 Log P (< 5): 3.76 HBD (< 5): 3 HBA (< 10): 4 MlogP (< 4.15): 3.00 Violations: 0 |

|

27

|

-7.49 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 377.48 Log P (< 5): 3.98 HBD (< 5): 2 HBA (< 10): 4 MlogP (< 4.15): 3.21 Violations: 0 |

|

28 |

-10.70 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 363.45 Log P (< 5): 3.72 HBD (< 5): 3 HBA (< 10): 4 MlogP (< 4.15): 3.00 Violations: 0 |

|

29 |

-7.11 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 363.42 Log P (< 5): 3.33 HBD (< 5): 3 HBA (< 10): 4 MlogP (< 4.15): 3.00 Violations: 0 |

|

30 |

-7.81 |

|

MW (< 500 Da): 363.45 Log P (< 5): 3.33 HBD (< 5): 3 HB A(< 10): 4 MlogP (< 4.15): 3.00 Violations: 0 |

MW: Molecular weight (Da), Log P: Octanol-water partition coefficient, HBD: Hydrogen bond donors, HBA: Hydrogen bond acceptors

The interactions analysis of the 12 best-docked ligands can be summarized as follows:

Other than hydrogen bonding interaction which is the main force among non-covalent interactions stabilizing the complexes [42], ligands 10, 11 and 12 show some similarities in interactions involving their aromatic rings. The presence of four aromatic rings in both compounds offers many possibilities for π-π interactions (stacked and T-shaped) to take place [43]. Other interactions such as π-alkyl interaction with VAL104, π-sigma interaction with ILE106, for all three ligands are established; and amide-π interaction with ASN151 for ligands 10 and 11. Ligands 10 and 12 are stabilized only by one hydrogen bonding interaction with GLN107 (ligand 10) and ARG105 (ligand 11) as the interacting residue of the amino acid. With regards to van der Waals (vdW) interactions as one of the main forces, six vdW interactions (GLN110, ARG 105, SER158, ASP153, ILE 152 and PHE8) occur in ligand 10, supported by two hydrogen bonds with GLN107 and ILE152 as amino acids residues. Six vdW interactions are also taking place in ligand 11 with ARG105, SER158, ASP153, PHE8, PHE294 and GLN110 as AA residues, while seven vdW interactions (PHE 8, ILE 152, ASN151, SER158, GLN107, GLN110, TH111 and ASP295) are identified in the complex ligand 12-Mpro.

Ligand 14 is characterized by one H-bonding interaction with GLN110, π-alkyl interaction with ILE249 and eleven vdW interactions with ASN203, THR292, ILE106, THR111, PHE 8, ASP295, ASN151, SER158, VAL104, PHE294 and CYS160. Surprisingly, none H-bonding interaction occurs in ligand 18, albeit the strongest one with the highest binding energy (12.26 kcal/mol). However, this ligand is stabilized by two π-alkyl interactions with MET165, CYS145, π-π interaction with HIS41 and ten vdW interactions with LEU141, GLY143, HIS164, ASP187, TYR54, GLN189, ARG188, THR190, GLN192 and GLU166. This result supports the works from Kasende et al, in which π-π and vdW interactions are primary forces in stabilizing two polyaromatic macromolecules, even when H-bonding interaction occurs [43, 44].

With none H-bonding interaction, except for ligand 22, one can refer to ligand 18 to understand the stability of ligands 21, 22, 23 and 24 with ΔG values between 10-11 kcal/mol. The complex formed between ligand 25 and the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro is stabilized by three hydrogen bonds with GLU166, CYS145, and HIS163 AA residues; a π-alkyl interaction with MET165 and six vdW interactions with interacting residues GLN192, GLN189, GLY143, ASN142, PHE140, and LEU141.

Finally, the complexes wherein ligands 26 and 28 are involved are stabilized by three (with LYS5, GLN127, LYS137 AA residues) and two hydrogen bonds (CYS145 and HIS163 being the AA residue), respectively. The stability of complex with ligand 26 is supported by a π-π interaction with TYR126 and six vdW with CYS128, GLY138, GLU290, SER 139, MET6 and VAL125, whereas the stability of complex with ligand 28 is supported by nine vdW interaction with ALA191, GLN189, THR190, GLN192, HIS164, GLY143, ASN142, PHE 140, LEU141.

3.2. Prediction of pharmacokinetics and toxicity

In the pipeline of computer-aided drug design, after the identification of hit molecules, the next step to deal with is the pre-clinical optimization that concerns the physicochemical properties, mainly the ADME/T prediction. The physicochemical property is an important parameter of a molecule which can be used as a drug and can be predicted by using Lipinski's rule of five (RO5) that is molecular mass < 500; Hydrogen-bond donors (HBD) < 5; Hydrogen-bond acceptors (HBA) < 10; and Log P < 5 [45]. Toxicity and pharmacokinetic studies such as absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of alkaloid compounds were assessed by using the web-based applications PreADMET (https://preadmet.bmdrc.kr/) and SwissADME database (https://www.swissadme.ch).

The drug-likeness properties accommodated in Lipinski’s rule of five of all ligands were calculated and are listed in Table 2. The results reveal that only ligand 14 does not fully obey Lipinski's rule of five criteria, with only 1 violation (MW 549.75 Da > 500 Da). Consequently, the best 12 docked ligands among the 30 investigated alkaloids may emerge as potential major inhibitors of COVID-19 protease.

Turning next to the pharmacokinetics and toxicity properties of eleven potential inhibitors ligands, the results displayed in Table 3 reveal that there are potential drug candidates (Table 3) among the 12 best-docked compounds. First of all, the hit molecule to be tested in the clinical phase must be non-carcinogenic. The rodent carcinogenicity in rat predicted by the preADMET server reveals that only ligand 22 is carcinogenic. The Ames test that assesses mutagenicity of a compound reveals that seven ligands are no mutagen, in addition to being no-carcinogenic: ligands 18, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26 and 28. Interestingly, the ligand 18 with the highest binding energy is predicted to be no-carcinogenic and no mutagen. The pharmacokinetic evaluation related to inhibition of Cytochrome P450 and substrate of P-glycoprotein shows that ligands 18, 21, 23 and 24 are found to be non-inhibitors of all CYPs. Ligands 10, 11, 12, 22, 25, 26 and 28 inhibit one or two of the cytochromes responsible for drug metabolism (CYP2D6 and CYP3A4), and cannot be presented as potent inhibitors drugs [46]. In the case of the hERG inhibition, all the ligands presented a medium risk. Thus, the toxicity prediction shows that the ligands 18, 21, 23 and 24 are safe and represent potential therapeutic candidates against COVID-19.

Table 3. Pharmacokinetics and toxicity properties of the three potential inhibitors.

|

Ligand |

Ames-test |

Carcino-Rat |

BBB p. |

hERG |

P-gp S. |

1A2 |

2C19 |

2C9 |

2D6 |

3A4 |

|

10 |

Mutagen |

Negative |

Yes |

Medium risk |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

11 |

Mutagen |

Negative |

Yes |

Medium risk |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

12 |

Mutagen |

Negative |

Yes |

Medium risk |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

18 |

No mutagen |

Negative |

Yes |

Medium risk |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

|

21 |

No mutagen |

Negative |

Yes |

Medium risk |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

|

22 |

Mutagen |

positive |

Yes |

Medium risk |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

23 |

No mutagen |

negative |

Yes |

Medium risk |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

|

24 |

No mutagen |

negative |

Yes |

Medium risk |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

|

25 |

No mutagen |

negative |

Yes |

Medium risk |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

26 |

No mutagen |

negative |

Yes |

Medium risk |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

28 |

No mutagen |

negative |

Yes |

Medium risk |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread in the world and most countries are currently facing the second phase of the virus propagation. Several strategies are used by researchers to help to find a solution to this public health issue. The present study used a computational drug design approach by molecular docking to identify potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease from a set of thirty alkaloid compounds from African medicinal plants as potential inhibitors. Scrutiny of the binding affinities leads to 22 hits with the highest binding energies, up to 12.26 kcal/mol, but pharmacokinetic investigations as an important pre-clinical phase reveal only four compounds as potential therapeutic agents to be used in the treatment of COVID-19: ligands 18, 21, 23 and 24. It should be noted that these four compounds have been isolated from Acistrocladaceae species, and their antimalarial properties have been confirmed by Bringmann and workers. Some traditional African healers use Acistrocladaceae species to treat measles and fever but so far no study has been carried out to support this use. To the best of our knowledge, this computational study is the first to report binding energies higher than 10 kcal/mol of ligands to bind to one of the pharmacological targets of the SARS-CoV-2. To support these encouraging results, we recommend further in vivo trials for the experimental validation of our findings.

Our sincere thanks go to Professor Kalulu M. Taba for agreeing to supervise this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any particular funding.

Supplementary Data

W. Ji, W. Wang, X. Zhao, J. Zai, X. Li, Homologous recombination within the spike glycoprotein of the newly identified coronavirus may boost cross‐species transmission from snake to human. Journal of Medical Virology 92 (2020).

N.J. MacLachlan, E.J. Dubovi, in Fenner's Veterinary Virology (Fifth Edition) (eds N. James MacLachlan & Edward J. Dubovi) (2017) 393-413.

F. Wu et al, A novel coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature (2020) 1-8.

H. Lu, C.W. Stratton, Y.W. Tang, Outbreak of Pneumonia of Unknown Etiology in Wuhan China: the Mystery and the Miracle. Journal of Medical Virology 92 (2020) 401-402. PMid:31950516

View Article PubMed/NCBIN. Zhu, et al, China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 382 (2020) 727-733. PMid:31978945

View Article PubMed/NCBIR. Lu, et al, Genomic characterization and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. The Lancet (2020).

M. Wang, et al, A precision medicine approach to managing Wuhan Coronavirus pneumonia, Precision Clinical Medicine 3 (2020) 14-21. PMid:32330209

View Article PubMed/NCBIL. Wenzhong, L. Hualan, COVID-19: Attacks the 1-Beta Chain of Hemoglobin and Captures the Porphyrin to Inhibit Human Heme Metabolism. Chemrxiv (2020) 11938173.

View ArticleP.T. Mpiana, K.N. Ngbolua, D.S.T. Tshibangu et al, Identification of potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease from Aloe vera compounds: A molecular docking study, Chem. Phys. Lett. 754 (2020) 137751.

View ArticleN. Chen, M. Zhou, X. Dong, J. Qu, F. Gong, Y. Han et al, Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 395 (2020) 507-13. 30211-7

View ArticleWorld Health Organization, Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report - 69 (Report). 29 March 2020. hdl:10665/331615

A.J. Rodríguez-Morales, K. MacGregor, S. Kanagarajah, D. Patel, P. Schlagenhauf, Going global -Travel and the 2019 novel coronavirus, Travel Med Infect. Dis. 33 (2020) 101578. PMid:32044389

View Article PubMed/NCBIK.N. Ngbolua, C.M. Mbadiko, A. Matondo et al, Review on Ethno-botany, Virucidal Activity, Phytochemistry and Toxicology of Solanum genus: Potential Bio-resources for the Therapeutic Management of Covid-19, Eur J Nutrition Food Safety 12 (2020) 35-48.

View ArticleD.S.T. Tshibangu, A. Matondo, E.M. Lengbiye et al, Possible Effect of Aromatic Plants and Essential Oils against COVID-19 : Review of Their Antiviral Activity, J Complem Altern Medic Res 11 (2020) 10-22.

View ArticleM. Alfaro, I. Alfaro, C. Angel, Identification of potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease from tropane alkaloids from Schizanthus porrigens: A molecular docking study, Chem. Phys. Lett. 761 (2020) 138068. PMid:33052144

View Article PubMed/NCBIA. Matondo, J.T. Kilembe, D.T. Mwanangombo et al, Facing COVID-19 via anti-inflammatory mechanism of action: Molecular docking and pharmacokinetic studies of six-anti-inflammatory compounds derived from Passiflora edulis, Research Square (2020).

View ArticleH. Lu, Drug treatment options for the 2019-new coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Biosci Trends. 14 (2020) 69-71. PMid:31996494

View Article PubMed/NCBIL. Zhang, D. Lin, X. Sun, U. Curth, C. Drosten, L. Sauerhering, S. Becker, K. Rox, R. Hilgenfeld, Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science (2020) 409-412. PMid:32198291

View Article PubMed/NCBIH. Yang, M. Bartlam, Z. Rao, Drug design targeting the main protease, the Achilles' heel of coronaviruses. Curr. Pharm. Des. 12 (2006) 4573-4590. PMid:17168763

View Article PubMed/NCBIR.K. Ganjhu, P.P. Mudgal, H. Maity, D. Dowarha, S. Devadiga, S. Nag, G. Arunkumar, Herbal plants and plant preparations as remedial approach for viral diseases. Virus disease 26 (2015) 225-36 PMid:26645032

View Article PubMed/NCBIR.R. Narkhede, A.V. Pise, R.S. Cheke, et al, Recognition of Natural Products as Potential Inhibitors of COVID-19 Main Protease (Mpro): In-Silico Evidences. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 17 (2020) 1-10. PMid:32557405

View Article PubMed/NCBIA. Onguéné et al, The potential of anti-malarial compounds derived from African medicinal plants. Part I: Anpharmacological evaluation of alkaloids and terpenoids. Malaria Journal 13 (2013) 449. PMid:24330395

View Article PubMed/NCBIM.H. Nkunya, J.J. Makangara, S.A. Jonker, Prenylindoles from Tanzanian Monodora and Isolona species. Nat Prod Res. 18 (2004) 253-258. PMid:15143836

View Article PubMed/NCBIM.R. Cao, M. Tits, L.M. Angenot, M. Frédérich, 17-O-acetyl, 10-hydroxycorynantheol, a selective antiplasmodial alkaloid isolated from Strychnos usambarensis leaves. Planta Med. 77 (2011) 2050-2053. PMid:21870325

View Article PubMed/NCBIG. Bidla, V.P. Titanji, B. Joko, G.E. Ghazali, A. Bolad, K. Berzins, Antiplasmodial activity of seven plants used in African folk medicine. Ind J Pharmacol. 36 (2004) 245-266.

O.O. Odebiyi, E.S. Sofowora, Antimicrobial alkaloids from a Nigerian chewing stick (Fagara zanthoxyloides). Planta Med. 36(1979) 204. PMid:482432

View Article PubMed/NCBIC.O. Okunji, M.M. Iwu, Y. Ito, P.L. Smith, Preparative separation of indole alkaloids from the rind of Picralima nitida (Stapf) T. Durand & H. Durand by pH zone refining countercurrent chromatography. J Liquid Chromatogr Relat Technol. 28 (2005) 775-783.

View ArticleM. Frédérich, M.P. Hayette, V. Brandt, J. Penelle, P.G. et al, 10'-hydroxyusambarensine, a new antimalarial bisindole alkaloid from the roots of Strychnos usambarensis. J Nat Prod. 62 (1999) 619. PMid:10217724

View Article PubMed/NCBIG. Bringmann, F. Teltschik et al, Ancistrobertsonines B, C, and D as well as 1,2-didehydroancistrobertsonine D from Ancistrocladus robertsoniorum. Phytochemistry 52 (1999) 321-332. 00130-2

View ArticleG. Bringmann, M. Dreyer et al, Ancistrotanzanine C and related 5,1- and 7,3-coupled naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids from Ancistrocladus tanzaniensis. J Nat Prod. 67 (2004) 743-748. PMid:15165131

View Article PubMed/NCBIG. Bringmann, K. Messer et al, Habropetaline A, an antimalarial naphthylisoquinoline alkaloid from Triphyophyllum peltatum. Phytochemistry. 62 (2003) 345-349. 00547-2

View ArticleG. Bringmann, W. Saeb et al, 5-O-demethyldioncophylline A, a new antimalarial alkaloid from Triphyophyllum peltatum. Phytochemistry 49 (1998)1667-1673. 00231-3

View ArticleG. Bringmann, M. Rübenacker, J.R. Jansen, D. Scheutzow, On the structure of the Dioncophyllaceae alkaloids dioncophylline A ("triphyophylline") and "O-methyltriphyophylline. Tetrahedron Lett 31 (1990) 639-642. 94588-X

View ArticleG. Bringmann, M. Rübenacker, R. Weirich, L. Aké Assi, Dioncophylline C from the roots of Triphyophyllum peltatum, the first 5,19-coupled Dioncophyllaceae alkaloid. Phytochemistry 31 (1992) 4019-4024. 97576-9

View ArticleO. Trott, J. Arthur, AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. J Comput Chem 31 (2010) 455-461. PMid:19499576

View Article PubMed/NCBIA. Daina, M. Olivier, V. Zoete, SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7 (2017) 42717. PMid:28256516

View Article PubMed/NCBIS.K. Lee, G.S. Chang, I.H. Lee, J.E. Chung, K.Y. Sung, K.T. No, The preADME: PC based program for batch prediction of ADME properties, EuroQSAR 9 (2004) 5-10.

M.L.Verdonk, J. Cole, M. Hartshorn, C. Murray, R. Taylor, Improved protein-ligand docking using GOLD. Proteins 52 (2003) 609-623. PMid:12910460

View Article PubMed/NCBIO. Trott, A.J. Olson, AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31 (2010) 455-461. PMid:19499576

View Article PubMed/NCBID.S. Biovia, Discovery studio visualizer, vol. 936, San Diego, CA, USA, 2017.

O.O. Olubiye, M. Olagunju, M. Keutmann, J. Loschwitz, B. Strodel, High throughput virtual screening to Discover Inhibitors of the Main Protease of the Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, Molecules 25 (2020) 3193. PMid:32668701

View Article PubMed/NCBIS.K. Enmozhi, K. Raja, I. Sebastine, J. Joseph, Andrographolide as a potential inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 main protease: an in silico approach, J Biomol Struct Dyn (2020) 1-7. PMid:32329419

View Article PubMed/NCBIO.E. Kasende, A. Matondo, J.T. Muya, S. Scheiner, Interaction between temozolomide and HCl: preferred binding sites, Comput. Theor. Chem. 1075 (2016) 82-86.

View ArticleO.E. Kasende, A. Matondo, J.T. Muya, S. Scheiner, Interactions between temozolomide and guanine and its S and Se-substituted analogues, Int. J. Quantum Chem. 117 (2017) 157−169.

View ArticleO.E. Kasende, V.P.N. Nziko, S. Scheiner, H-Bonding and Stacking Interactions between Chloroquine and Temozolomide, Int. J. Quantum Chem. 116 (2016) 1196.

View ArticleD. Lagorce, D. Douguet, M.A. Miteva, B.O.Villoutreix, Computational analysis of calculated physicochemical and ADMET properties of protein-protein interaction inhibitors, Sci. Rep. 7 (2017) 46277. PMid:28397808

View Article PubMed/NCBIY.C. Martin, A bioavailability score, J. Med. Chem. 48 (2015) 3164-3170. PMid:15857122

View Article PubMed/NCBI